Week 3 [Mon, Jan 23rd] - Programming Topics

Functions

Writing Functions

You can write your own functions in Python. Function are useful when you want to execute a bunch of statements multiple times at different points of a program.

Format:

def function_name():

statement_1

statement_2

...

The code below defines a function named say_hello and calls it twice.

| → | [Click here to visualize the execution] |

Note how the statements inside the function are not executed unless the method is called.

The function definition should appear in the code before it is called.

Good (this works) | Bad (this will not work!) |

Function Parameters

You can configure a function to have parameters. The code inside the function can use the parameters like variables. That means we can pass arguments (i.e., values for those parameters) to affect the behavior of a function so that the function behaves differently each time it is executed.

Format:

def function_name(parameter1_name, parameter2_name, ...):

...

Parameters vs arguments: When you define a function, you can specify parameters that it can accept. When you call the function, you can assign arguments (i.e. values) to each of those parameters.

The say_hello function below takes one parameter. The first time we call it we pass the argument Gina to that parameter, and the next time we pass a different argument John to the same parameter.

| → | [Click here to visualize the execution] |

The code below has a say_hello function that takes one parameter and a repeat_hello function that takes two parameters. Furthermore, note how one function calls the other.

def say_hello(name):

print('Knock knock ' + name)

def repeat_hello(name, times):

print('Greeting ', name, times, 'times')

for i in range(times):

say_hello(name)

repeat_hello('Penny', 3)

say_hello('Sheldon')

Knock knock Penny

Knock knock Penny

Knock knock Penny

Knock knock Sheldon

Parameter values are forgotten after the function returns.

The code below produces an error because variable v1 is not available after the function has returned.

def print_uniqueness(v1, v2, v3):

print(v1 != v2 and v2 != v3 and v3 != v1)

print_uniqueness(1,2,4) # True

print_uniqueness(1,1,2) # False

# Error. v1 is not available after function returns

print(v1)

Return Value

You can use a return statement to make a function return a value.

The play() function below returns one of the strings Rock, Paper, Scissors randomly.

import random

def play():

value = random.randint(1,3)

if value == 1:

return 'Rock'

elif value == 2:

return 'Paper'

else:

return 'Scissors'

print('Player1 response : ' + play())

print('Player2 response : ' + play())

You can use an empty return statement to return from the function without executing the remainder of the function, even if the function does not return anything.

The print_all_products function below uses an empty return statement to return from the function early if one of the arguments is 0:

def print_product(a, b):

print(a, 'x', b, '=', a*b)

def print_all_products(n1, n2, n3):

# return early if any value is 0

if n1 == 0 or n2 == 0 or n3 == 0:

print('Values cannot be zeros')

return

# print all possible products

print_product(n1, n2)

print_product(n2, n3)

print_product(n3, n1)

print_all_products(2,3,4)

print_all_products(0,2,3)

Local and Global Scope

The scope of a variable is which part of the code it can be read/modified. Think of a scope as a container for variables. When a scope is destroyed, all the values stored in the scope’s variables are forgotten.

The global scope is the scope that is applicable to the entire program. There is only one global scope, and it is created when your program begins. When your program terminates, the global scope is destroyed, and all its variables are forgotten. Otherwise, the next time you ran your program, the variables would remember their values from the last time you ran it. A variable that exists in the global scope is called a global variable.

A local scope is a scope that applies only during the execution of a function. A local scope is created whenever a function is called. Parameters and variables that are assigned in the called function are said to exist in that function’s local scope. A variable that exists in a local scope is called a local variable. When the function returns, the local scope is destroyed, and these variables are forgotten. The next time you call this function, the local variables will not remember the values stored in them from the last time the function was called.

A variable must be in the global scope or the local scope; it cannot be in both.

[Some parts of the above explanation were adapted from Automate the Boring Stuff]

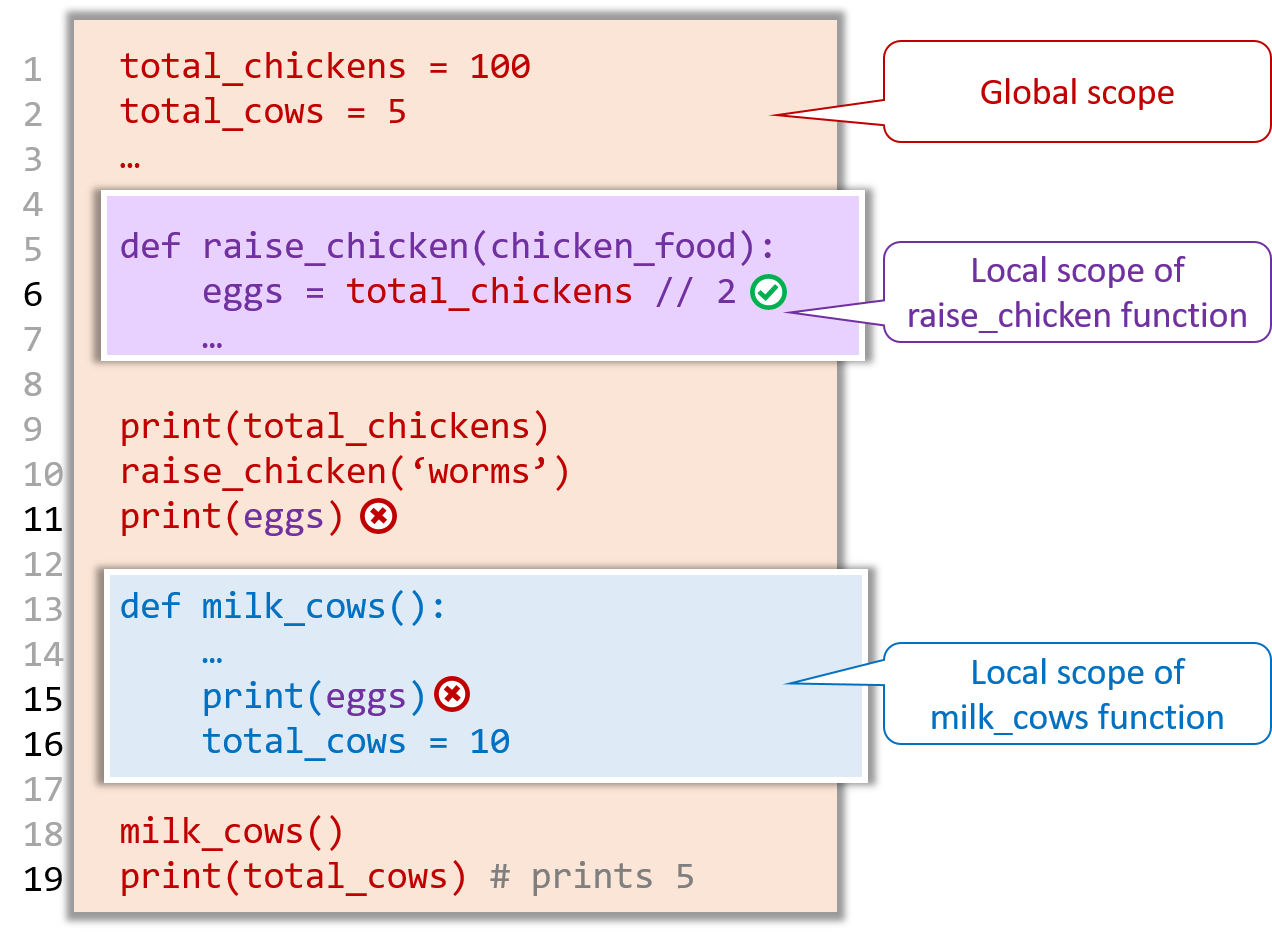

Consider the code given below (apparently, from a program related to a farm). The global scope and the local scope of each function indicated by shaded areas.

Note the following rules about scope:

- Rule 1: Local scopes can read global variables e.g.,

raise_chickenfunction can access the global variabletotal_chickens(see line 6). - Rule 2: Global scope cannot read/write local variables e.g., line 11 will be rejected because it reads the local variable

eggs. - Rule 3: Local scopes cannot read/write variables of other local scopes e.g., line 15 will be rejected because it reads the local variable

eggs. - Rule 4: If a variable is assigned in a local scope, it becomes a local variable even if a global variable has the same name. That is, there can be separate global and local variables with the same name. e.g., line 16 (

total_cows = 10) creates a local variabletotal_cowsalthough there is also a global variabletotal_cows; the line 19 prints5because thetotal_cowsglobal variable remains5and the local variabletotal_cowswhich has the value10is destroyed after the functionmilk_cowsis executed.

To modify a global variable within a local scope, use the global statement on that variable.

The breed_cows function below can increase the global variable total_cows to 10 from the local scope because it has a global total_cows statement. If you remove that statement, the last print statement will print 5 instead of 10

total_cows = 5

print('total cows before breeding:', total_cows)

def breed_cows():

global total_cows

print('breeding cows')

total_cows = 10

print('total cows at the end of breeding:', total_cows)

breed_cows()

print('total cows after breeding:', total_cows) # prints 10

| without the |